Focus ROMI.HR

/The horrors of WWII led to the creation of the word “genocide” and new international laws to deal with such crimes. Proving intent behind mass killings is still tricky and often debated. Visiting Jasenovac makes the reality of those crimes hit hard... it's something you don’t forget.

The horrors of the Second World War resulted in the murder of millions of people in concentration camps by the Nazis, together with the Italian Fascist forces led by Benito Mussolini and other various collaborationist groups and governments that supported Hitler’s Nazi regime, like the Ustaša one in Croatia.

The systematic elimination of specific groups, mainly the Jews, but also Roma, people with disabilities, homosexuals, political dissidents, Poles, Serbs, and prisoners of war, resulted in millions of victims and crimes of unprecedented dimensions that required new legal frameworks to be adjudicated upon, and for those who committed these crimes to be condemned adequately.

That is why the Second World War had a significant impact in making International Law advance as a discipline: because scholars and judges were dealing with the challenge of creating a whole new set of rules (and crimes) from scratch. The first step in this direction was the establishment of two international military tribunals, one in Nuremberg (Germany) and one in Tokyo (Japan), to prosecute the crimes of the Axis powers during the War. The impact of these tribunals went further than their originally declared scope, as they contributed largely to the formation of a whole new branch of international law, called International Criminal Law.

International Criminal Law (from now on: ICL) aims at ensuring justice to victims of serious international crimes, and to promote peace and security through the accountability of criminals and deterrence of future crimes. However, since this branch of law was almost completely new, experts had to first lay the basis of the discipline: put simply, they needed to decide which crimes were included in the framework of ICL. Those discussions paved the way for what ICL still is today, and the four “core crimes” identified by scholars and lawyers are still used to the present day to understand whether ICL is applicable to certain crimes or not.

The four “core crimes” are genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and aggression. All four of them are of great relevance and target horrendous crimes, but for the scope of this article, we will only focus on genocide.

Before the Second World War, the concept of genocide did not exist: indeed, even if atrocities had been committed during wartime in the past, none of them was even slightly comparable to the extermination of people committed by the Nazis and their allied forces. The greatest example in this sense is the fact that there was not even a word to describe this kind of crime, and that the word genocide was created by a Polish lawyer, Rapahel Lemkin, in 1944 by combining the Greek word for people (genos) and the Latin suffix for to kill (-cide). Lemkin felt a strong, personal connection to the Holocaust and the extermination of other groups, as he had also lost several members of his family because of the same mass killings.

Soon after, the Nuremberg trials first and the United Nations later, adopted the term genocide not only to describe the extermination policies that took place during the Second World War, but also as a fundamental concept from a legal perspectives. Additionally, Lemkin did not just contribute to the creation of the term: he also was in the team that identified the elements that must be present for a crime to be qualified as genocide.

All these criteria have been formally written in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, adopted by the United Nations in 1948. Article 2 of the Convention defines the crime of genocide as “any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

a) Killing members of the group;

b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

Even if the definition may seem very clear and easy to use, we should not forget that the idea of genocide is very strong and powerful, and there are often debates over whether a particular crime should be considered as an example of genocide or not. For this reason, experts tend to add more details to what has been established in the Convention when evaluating if a genocidal crime is at place or not.

More specifically, lawyers have insisted on the fact that it is crucial to prove that the killing of people (or all the other ways of destroying the targeted group listed before) was intentional, that there was a direct motivation to exterminate a group. This is the most problematic part of the definition, because it is difficult to prove that intent was present; it is also the reason why International Courts are often reluctant to use the word 'genocide'.

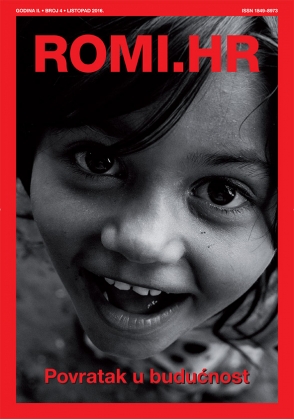

However, all these theoretical elements fade when one is put in front of the traces of what a genocide was. That is what happened to me during our visit to the concentration camp of Jasenovac, put in place and led by the Ustaša government of the Independent State of Croatia. Jasenovac is today a small village at the border with Bosnia and Herzegovina, but the marks left by the genocide committed by the Ustaša forces, mainly against Jews, Serbs, and Roma people, are still very present.

.jpg)

.jpg)

For me, it was the first visit ever to a concentration camp, and it was a shocking experience. I felt overwhelmed by horror, sorrow, grief, and sadness. I couldn’t stop wondering how humans can be animated by so much hatred and the desire to exterminate others. This also made me reflect even more on the role of International Law: conflicts did not stop after the Second World War, racism is still present, and some groups are still victims of persecution and mass killings because of their religion, skin color, or ethnicity. We live in a world in which we like to think that war is a thing of the past, but in reality, it is not.

Laws and conventions are fundamental to try to put some order in our societies, but they can do little to change the minds of those who still believe that some groups are superior and deserve to live more than others. I could not believe that nobody could be saved from that atrocity, that even children were sentenced to death simply because their existence was a threat. At the Jasenovac Memorial Museum, I read the stories of young lives cut short, kids forced to live in camps who tried to find a glimpse of normality in creating tiny drawings in their notebooks, couples who were divided forever, and lives haunted by loneliness and fear.

And what is even worse is that there are so many people who have been exterminated whose names we don’t even know. They are just anonymous bodies, deprived not just of their lives, but even of their identity. It is the case for many Roma people who remain unknown, unidentified, forever erased because we cannot even call them by their name.

I believe that if more people visited places like Jasenovac, the brutalities committed by Fascist and Nazi governments would be so evident that nobody would even dare to celebrate these regimes. Unfortunately, it is easier to forget and try to justify, at the risk of a new cycle of violence and hatred emerging in the future. That is why it is important to remember and to pay homage to the victims of this horror: because we can all become members of a targeted group, somewhere, somehow, just because of who we are.

Photo Gallery:

Back to Focus

Back to Focus

.jpg)

_400_225_80_s_c1.jpg)