Focus ROMI.HR

/In the 19th century, the Russian Empire gradually shifted from granting the Roma exemptions from taxes and conscription to enforcing repressive assimilation policies, especially under Nicholas I. Efforts included forced settlement, child recruitment into military schools, and integrating Roma into military service to ensure control and state loyalty. While these measures disrupted Roma communities and traditions, they also introduced some to education and upward mobility within the army, ultimately leading to their formal inclusion in the national conscription system by 1856.

A new chapter in the history of Roma in the Russian Empire was opened by the military duty of country's residents.

The inclusion of the people in the urban and rural classes (peasants, townspeople, merchants) implied an obligation to conscription in money equivalent or in the form of army attendance (conscription - the system of army and navy recruiting in Russia in the 18 -19 centuries). It was one of the factors of societal unity and the state order. However, the Roma, unlike other ethnic groups, did not represent one unified people. This fact forced the government to take a different approach to their recruitment duties.

By the end of the 1820s - beginning of the 1830s the situation of different Roma groups varied. On the one hand, the newly gained ethnic population of the Russian Empire received national estates and with them all the accompanying rights and obligations. On the other hand, the annexation of new lands required caution in political decisions, therefore, the assimilation of the acquired territories was accompanied by the preservation of the previous rights and obligations for the Roma and, thus, the presence of some advantages.

In 1828-1829 by the decision of Bessarabian and Novorossiysk officials, the Roma were exempted from paying taxes and military contributions for 4 years. The absence of conscription was continuing since the signing of the Decree on the formation of the Bessarabian region in 1818. The reason for such concessions was another dissatisfaction with the nomadic way of life and attempts to peacefully integrate Roma into a settled living.

By the time of the 1820-30s, the governmental plan was more or less successful: Roma were a semi-sedentary people. The situation varied from region to region due to political oppression of past centuries. Since the Roma traveled in families and were always on the road, they did not have a sense of ethnic unity with other camps. Thus, some of them accepted the proposed ranks and tried to start a new life, others rejected changes and fought for the freedom to choose their place of living.

At the same time, exemption from conscription and other monetary obligations also spreaded to residents of Feodosia and Odessa due to the need of the economic importance growth of those places as a Black Sea port. However, the benefits did not end in Bessarabia and Crimea. In the Caucasus, the authorities also made concessions to the Roma. Those living in the villages of the Caucasus were under threat of attack by the mountaineers. At the end of the 1820s the Pyatigorsk district was devastated. The Roma became direct participants in the fight for land on an equal basis with everyone else. This was the reason for the appeal of the head of the Caucasus region E.I. Mechnikov to the Minister of Finance E.F. Kankrin with a request to forgive Roma for non-payment of state and local taxes due to financial and human losses. At the same time, the people were exempted from conscription duty.

Moreover, in 1831, the Recruitment Charter was updated, according to which exiled settlers in Siberia received benefits in the form of exemption from military service and payment of duties for 20 years from the date of settlement. Among such people were also Roma. In this case, the reason for the benefits was the need to populate hard-to-reach territories that needed to be filled with people.

By the beginning of Nicholas 1 governance, a repressive policy against nomadism began. Directly related to the militarization of ethnic groups, it was preceded by a complex of reasons. One of the main factors was public rejection of the privileges provided to Roma. Most likely, society was not happy with the fact that one group of people lived a freer life. People didn’t see their benefit from it.

Thus, complaints were received against Roma to government institutions. Moreover, Nicholas I's reign was characterized by a strict adherence to autocratic rule and a desire for a disciplined, obedient society. The state sought to improve governance, enhance control over nomadic groups, and encourage assimilation into mainstream Russian society. The notion of a settled lifestyle was viewed as more conducive to state control and integration.

Nicholas 1 outlined an extensive plan of action. He ordered a collection of all Roma living in the Russian Empire and a forced distribution of one or more families to each settlement, depending on capabilities. The emperor ordered that the issuance of passports, without which it was impossible to travel further than 30 versts (32 km), can be allowed after Roma had completely taken root in the village and to no more than one person from the family.

In 1832-1834 legislative acts appeared on the basis of which new orders came out. The police had to detain nomadic people and womderers to be recruited or sent to cantonist schools (low-level military educational institutions). In 1832, one of the first Senate Decrees was issued, in which a large part was devoted to actions against juvenile wonderers (under 17 years of age). They had to be sent to canton battalions and half-battalions, the minimum age limit of whom was 8 years old. The first legal instructions were sent to the Don and Bessarabian administrations, which later spread throughout the country. This measure applied to both single young wonderers and those who were with their families.

In 1834, a new repressive order was issued in the Belarusian-Lithuanian provinces. Urban and rural societies, local landowners were required to notify the police of anyone who was illegally assigned to the estates or was in their area of responsibility without identification documents. Those who were on this list were ordered to be transferred to the jurisdiction of the military authorities. Healthy Roma were sent to military service, the rest were sent to military prison companies. Women and children were transferred to factories and military settlements.

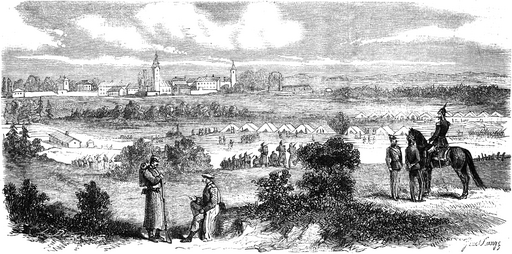

Thus, in the 1830s, numerous correctional companies were created, which were staffed by nomadic and homeless people. According to the personal decree of Nicholas 1, the first three companies were formed from the Roma of the Tauride province. In a short time, about 300 Roma were assigned to the military correctional service.

In 1840, the governor of Vyborg (north-eastern part of the Empire) presented to Nicholas 1 a traditional report on the life of the province and its population. In particular, attention was paid to the Roma children, who were more than once seen on the streets alone. As a result, it was decided to send Ingrian Roma from 8 to 17 years of age to the St. Petersburg battalions of military cantonists. During 1842-1853 About 16 Roma were sent to St. Petersburg.

Without a doubt, sending children to St. Petersburg became a culture shock for them. The boys who arrived mostly did not speak Russian, were cut off from their families, their usual daily environment and their cultural vacuum; Roma newcomers befriended those who were in the same position. Their whole life was turned upside down and became very stressful. All this made the process of adaptation to new conditions very difficult.

However, this policy also had its advantages. Children co-opted into the military system were almost for the first time involved in the educational process. While undergoing military service, they were required to receive primary education. Those who successfully passed the exams and practical tests were sent for further military service to the positions of sergeant majors and non-commissioned officers, all others were enlisted as soldiers with the subsequent opportunity to receive the rank of non-commissioned officer. Hence, the military-political campaign bore fruit. The Roma who served, due to their small numbers, were for the most part assimilated, since they did not have their own stable ethnic core, unlike the Jews.

At the end of the reign of Nicholas 1, in January 1856, a final opinion was developed on the submission of Roma to the Russian Empire for conscription. Having consolidated many years of practice, the State Council formalized the opinion that Roma are an integral part of society, and therefore should bear recruiting duties on an equal basis with everyone else. The exceptions were those who were classified as a merchant guild and were completely exempt from recruitment duties in any form. The Roma of Tavria had a special position, they were allowed to replace physical participation in conscription with money. The reason was that the Roma of Tauride were classified as state peasants, professed Islam and were co-opted into the Tatar communities, which gave them a special position.

Back to Focus

Back to Focus