Unsplash

Unsplash In the 1960s, Italy launched special “Lacio Drom” classes to improve schooling for Roma children. These classes, promoted by Opera Nomadi in collaboration with universities and the state, focused on language, mathematics, and practical skills. They were also tied to the Catholic Church’s goal of evangelization and integration into Italian society. The project, active until the early 1980s, had mixed results but remains a milestone in Roma education in Italy.

In 1965 the economy in Italy was booming, the country had already started learning the dynamics of being a democracy and a republic, and everybody was working hard to leave the destruction and brutalities of the Second World War and of fascism behind. The Roman Catholic Church was still exercising a great level of influence on the country, not only on Italian internal politics, but also by being extremely active in society, with the attempts at improving the living conditions of all individuals, especially those facing poverty or lower chances to access higher education.

During the Second World War, Roma people experienced very harsh treatments from Fascist authorities, including internation, some killings, and many of them ended up in concentration camps or labor camps, where they suffered serious shortages of food, which sometimes ended up in starvation. Their accommodations were inadequate, and they were often victims of various forms of physical and mental abuses. Therefore, from 1945 to the early 1960s, Roma people shared difficulties of most Italian citizens, but in addition, they were also victim of racist behaviors and systematic exclusion from society.

In this context, a story is of particular interest: that of Lacio Drom classes. In early 1960s, members of Italian politics and Universities, led by a religious organization, tried to increase the living standards of Roma children by designing a specific type of classes meant to introduce them to Italian language and to teach them some basic notions in the fields of mathematics, geometry, science, history, and geography.

The first trace of Lacio Drom classes can be found between Trentino Alto Adige, in Northern Italy, and Tuscany, in Central Italy. Indeed, Bruno Nicolini, a priest who was responsible for implementing the Church’s efforts to evangelize Roma peoples in Italy, also through social activism, first elaborated this educational program. Thus, in 1965 Nicolini founded Opera Assistenza Nomadi (Nomad Assistance Work), later renamed Opera Nomadi (Nomad Work), an institution recognized by the Italian state whose main goal was to introduce Roma pupils to school. It is noteworthy that this educational process was not merely about offering Roma the possibility to take Italian classes or to learn more about Italian history; rather, the underlying scope was to transform them into Christians by transforming them into Italian citizens first. To sum up, Nicolini’s idea was to evangelize Roma families by making them interact with other Italian families who were Christians by definition, especially in a moment in which the Catholic Church was still quite influential.

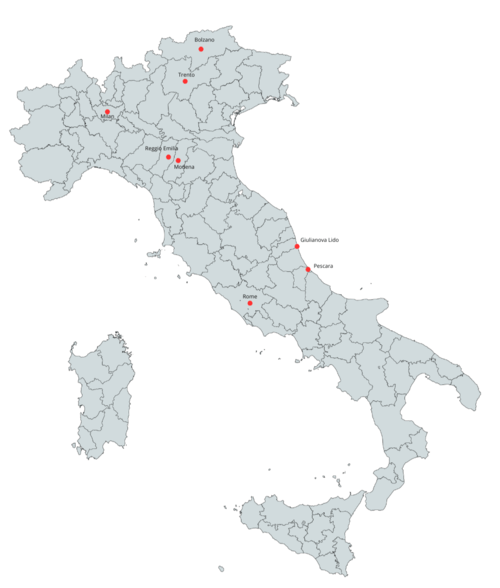

In 1965, Nicolini’s Opera Nomadi started cooperating with the University of Padua and the Italian Ministry of Public Education to create Lacio Drom classes all across Italy. In the first year of the Lacio Drom project, two special classes were already active in Bolzano, in the very north, and some more were opened, two of them in Rome, then in Pescara and Giulianova Lido, both in central Italy, near the Adriatic coast, Reggio Emilia and Modena, halfway between the North and the Centre of the country, Milan, and Trento, in the north of Italy, 80 km south of Bolzano. Some individuals cooperating with Opera Nomadi were already present in these cities; hence, it was easier to set up the first Lacio Drom classes there.

The first cities hosting Lacio Drom classes, in 1965.

According to the founding agreements, these classes had the primary scope of promoting schooling among Roma children. The well-functioning of classes was mainly in the hands of those teachers who were in charge of teaching: indeed, they had to attend regular refresher courses to discuss what pedagogical approach to be adopted when teaching Roma children. Collaborators from Opera Nomadi were crucial to implement the project, because they ensured that children would actually participate to classes, by taking care of vaccination, helping Roma families get parking permits for their caravans, encouraging Roma parents to send their children to school, and by raising awareness about integration and stereotypes among teachers and parents of gagé children. The term gagé is used by Roma in Italy to refer to people who are not part of Roma community, but this term started to be used also by teachers when they were talking about non-Roma pupils.

The agreement between Opera Nomadi, the University of Padua, and the Ministry of Public Education also established the school subjects and the topics that teachers were supposed to teach pupils. In comparison with ‘ordinary’ classes, the Lacio Drom ones focused more on practical lectures rather than on theoretical ones. For example, the classes on Italian language were devoted to help pupils become “functional”, well-adjusted, individuals, instead of introducing them to Italian culture or society. Similarly, math classes concerned how to write money orders and exercises on how to use money in general.

Science classes focused on a mix of basic notions (such as the flora and fauna of regions) and explanations on the functioning and scope of various household appliances. During history lectures, teachers had to instruct pupils on the history of Roma populations and of the biggest ancient civilizations (like the Egyptians, the Greeks, and the Romans). Interestingly enough, the program also included some hours of civic education, in which teachers explained the roles of the President of Republic and the Pope, the differences between the republican and monarchical systems, the functioning of the government and the parliament, to eventually conclude by presenting the main articles of the Italian Constitution. Geography classes were the closest to the ones held for other Italian children, with the addition of some classes on basic notions regarding Italy and the specific region and city in which the pupils were staying at that time.

Six years after the beginning of the project, in 1971, Lacio Drom classes in Italy were 59. Compared to the first ones opened in 1965, the 1971 edition of the project had extended also in the southern part of the country that, then as now, was significantly poorer than the northern and central areas of Italy. This pre-existing gap between the North and the South of the country may also explain why it took some years before some Lacio Drom classes actually appeared in regions like Calabria and Basilicata, where Roma families had already been present for many decades.

Special classes for Roma pupils remained open and active until the late 1970s, when the debate among teachers and the 'sponsoring' organizations started pointing out at the flaws and the lack of results of the project, especially due to the low numbers of Roma children that were going to classes consistently. At that moment, the envisaged solution was to overcome special classes, and rather to work jointly to ensure a smooth inclusion of Roma children in 'ordinary' classes.

The idea of making Roma children interact with all other kids from 'Italian' families was functional to their improvement as students and, most importantly, their personal growth as individuals. By having to work and spend time with children from other backgrounds was fundamental for Roma children to feel encouraged to study more, to learn more things, to speak better, to make new friends. At the same time, Italian children learned Roma traditions and culture, and this was more than helpful in trying to mitigate anti-Gypsism biases and stereotypes that were unfortunately quite common in Italy.

Lacio Drom classes closed permanently in the early 1980s, ending an almost twenty-year long project, with mixed results. Notwithstanding some of the issues that characterized the realization of special classes for Roma children, learning more about this ground-breaking project experimented by Italy between the 1960s and 1980s can be helpful to find new ideas on how to ensure higher level of education and cultural integration of Roma in Italy and all across Europe.