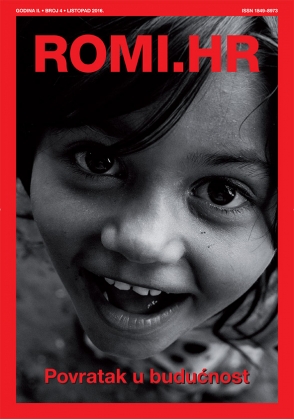

Fokus ROMI.HR

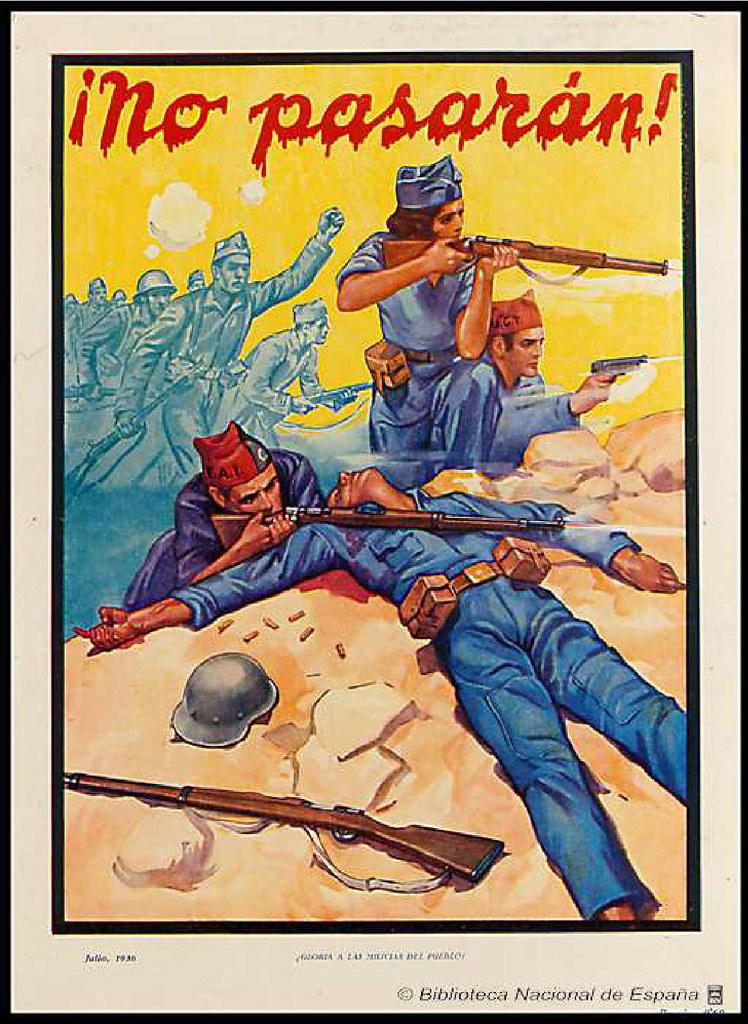

/The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) began with the uprising (levantamiento) of the fascist National forces against the democratically elected Second Republic on the 18th July 1936. The bloody struggle ended with the defeat of the Republic and coming into power of Francisco Franco, who was to lead a dictatorship in Spain that lasted until his death in 1975.

In the early moments of the war, the defence of Barcelona was of huge importance. The National Confederation of Labour (CNT), an anarcho-syndicalist union created in 1910, initially succeeded in maintaining left-wing power in Barcelona and Aragón against the fascists. Many CNT members saw the potential of ‘’a por el todo’’ (going for all) policy of action. ‘’A por el todo’’ was based on the perceived opportunity for complete social revolution and the creation of an anarchist system of production in Spain. A key dimension of the process for anarchist leaders was to decide whether to pursue this policy or join forces with the Republic’s government in the war struggle against the fascist National side. Joining forces (known as the collaborationist approach) implied prioritising war victory over the revolutionary process. In other words, the revolution would have to wait until the war was won.

Despite receiving strong opposition and criticism, collaborationism eventually became the main path for the CNT and other libertarian groups. A number of prominent anarchist leaders were appointed as ministers in the Republican government of Largo Caballero. This decision had serious consequences for the war development in Spain. A central figure in this process, seriously understudied in Spanish Civil War history, was Mariano Rodríguez Vázquez, known as ‘’Marianet’’. His role as Secretary General of the CNT during the war, shaped by his close ties with President of the Republic Juan Negrín after 1937 and a strong preference for the collaborationist way, affected the way in which the war was fought and perhaps even its final outcome.

Marianet was born in the proletarian neighbourhood of Hostafrancs (Barcelona) in 1908. A childhood full of hardships instilled a strong sense of resilience in him. Following his mother’s death and his father’s abandonment, he escaped a reformatory where he frequently faced abuse. His desperate resort to petty crime led him to prison multiple times. During his time in jail, he became deeply connected to libertarian ideas, which led him to join FAI (Iberian Anarchist Federation) in 1931. During the Civil War, his meteoric rise culminated with Marianet becoming Secretary General of the National Confederation of Labour (CNT) in November 1936. Marianet, who was Roma, had considerable political influence and responsibility given this position. This situation comes in clear contrast with the stereotypical narrative which has often portrayed Roma people as politically detached throughout the Spanish Civil War, and is worth exploring in connection with the Popular Front’s internal struggles.

A few months before Marianet’s announcement as Secretary General, the initial attempt by the fascists to take Barcelona in July had been repelled by the CNT, pro-anarchist forces and workers’ self-organised militias. Fearful that anarchist control over Barcelona could expand to other places and overthrow the Republican government in Catalonia, Lluís Companys (its president) agreed with the anarchists to form the Central Committee of Anti-Fascist Militias of Catalonia (CCMAC). This entity, which included all anti-fascist political groups (known as the Popular Front) and was designed to organise joint military resistance against fascism, was dominated by anarchists. At the same time, it served to legitimise the Republican government in Catalonia, which would now operate through the newly established CCMAC. Collaborationism was therefore set to impose itself, and as a result the revolutionary tendencies of anarchist bases would be contained by their own leaders’ access to institutional power structures.

.jpg)

This way, anarchist leadership entered a political space where anti-anarchist hostility was common among Communists in the CCMAC, represented by the Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia. The need to make concessions given PSUC distrust of anarchists and protect the unity of the Popular Front included an undermining of the autonomy of revolutionary committees in Catalunya and Aragón, whose collectivisation efforts were not adequately supported by anarchist leaders. By the end of September 1936, the CCMAC was abolished in favour of a restored Catalonian Republican government with anarcho-syndicalist participation.

Marianet, then leader of the Regional Committee of the CNT in Catalonia, presented this decision to the anarchist bases as guided by the need to safeguard and expand the revolutionary spirit through temporary collaboration with government forces, considering that ‘’in other parts of Republican Spain anarchism was not as powerful’’ (Ealham, 2011). On the 26 of September, three anarchists joined the new Catalan government. Similarly, the CNT National Committee decided (without consultation with the bases) to appoint four anarchists to the Central government.

These actions implied a considerable shift away from ‘’pure’’ libertarian thinking which advocated for opposition to any form of government and went against a ‘’a por el todo’’ policy of social revolution. Would this new route serve, as Marianet had explained, to strengthen not only the Popular Front as a whole but also the anarchists in their quest for revolution?

TBC.

Galerija slika:

Povratak na Fokus

Povratak na Fokus

_400_225_80_s_c1.jpg)