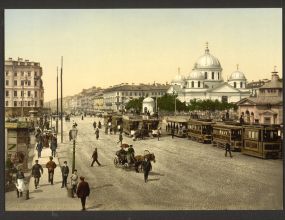

Dawn Hudson - CC0 Public Domain

Dawn Hudson - CC0 Public Domain The Russian Empire’s attempts to settle the Roma largely failed due to mistrust and strong nomadic traditions. Catherine the Great introduced stricter controls, but resistance remained. In the 19th century, limited freedoms allowed partial integration as artisans and merchants.

The initial efforts of the Russian Empire to sedentarise the Roma population, starting from the reign of Anna Ioannovna in the early 18th century, didn't succeed. The Empire's attempts were primarily driven by financial motivations and a desire to integrate the Roma into the state structure. Various measures were introduced, including the collection of taxes from Roma and attempts to settle them on fertile lands. However, these policies largely failed due to a lack of trust from the Roma, the inefficiency of the collection systems, and the deeply ingrained nomadic lifestyle of the Roma people.

The accession of Catherine the Great brought new strategies, including the establishment of the Pale of Settlement, aimed at limiting the movement of Roma to specific regions. Despite these efforts, the Roma continued to resist sedentarisation, valuing their freedom and nomadic traditions over the imposed regulations.

The year 1783 marked another attempt to assimilate Roma. The ruling Senate of the Russian Empire decided that all Roma should have equal rights with state peasants, and the responsible director of housekeeping must find pieces of land for nomads, convince them to settle in one place and engage in agriculture.

Despite formal restrictions, Roma gradually settled in provinces and cities, actively conducting trade and their usual way of life. This caused opposition and displeasure from local merchant and noble circles, who repeatedly lodged appeals to the government. Moreover, the population of Roma, with its traditions, orientation towards trade and illegal fishing, combined with the organization of self-government, with great difficulty fit into the imperial administrative system, in particular into the class division. They still could not be classified either as merchants (city dwellers) or as peasants.

The central and provincial administrations faced a number of management problems regarding the determination of their places of residence. The way to solve all these problems was to limit settlement to places where they had previously been ordered to live. Thus, on December 23, 1791, Catherine the Second introduced the Pale of Settlement. The Pale of Settlement is a restriction on movement of the Jewish and Roma people, prohibiting them from traveling outside the western and central provinces. The reason for this was most likely the desire for economic development of new territories and the accompanying assimilation of the population.

On one hand, Roma saw a catch in everything that was prepared for them and, most likely, suffered numerous losses. The fight for the right to decide one’s life took a lot of financial, physical and moral resources. On the other hand, the era of Catherine the Great is a time of adherents of the ideas of enlightenment, which means equalization of the rights of various groups of the population. What Catherine the Second tried to do, in her eyes, was a positive change for those to whom the new decrees and instructions were addressed. The downside of the system was the imperial administration’s unwillingness to competently integrate the peoples who came with the new lands.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the policy regarding Roma constantly changed its vector. Initially, it was decided to assign Roma to the land on whose territory they found themselves during the population census. Thus, after a revision of a particular territory, if Roma was assigned to it, they turned out to be the property of the landowner. In 1800, an order was issued banning the issuance of identification documents to Roma, and in 1803 the Governing Senate issued a corresponding decree. Those Roma who, according to census, were not assigned to the landowner, were to be divided into small groups and distributed among the villages.

Despite the fact that great efforts were made to combat the nomadic way of life, the Roma did not give up their positions and refused to obey. They fled from the landowners in search of their former freedom and reunification with their family, forcing the landowners to incur financial losses in transportation and search for them.

Taken actions did not produce the desired results. Then it was decided to free the landlords from the ownership of Roma and assign them to the cities. Now, according to the law, Roma who did not have identification documents could freely enroll as artisans, burghers, state peasants, and merchants. Roma were given relative freedom of action; the main prohibition was to continue to lead a nomadic lifestyle. In case of a Roma family being absent, the one who issued them tickets had to pay a ruble to the Order of Public Charity, and the Roma who escaped were searched for and returned back.

At this stage, the policy became relatively successful for both sides, since some of the Roma were actually able to find a decent life by those standards.

Most of the ethnic group became artisans and merchants, as the Roma had high skills and an intuition for such types of activities. Moreover, the nomadic movements of the people narrowed to a limited territory, from which they became part of the Empire.

A new chapter in the history of Roma in the Russian Empire was opened by the military duty of residents of the country's regions.