Author: census 2001 via Wikimedia Commons

Author: census 2001 via Wikimedia Commons Monarhija u Bugarskoj je službeno ukinuta u rujnu 1946. godine. Komunistička partija preuzela je gotovo potpunu kontrolu nad zemljom, a država je proglašena Narodnom Republikom. Povijesno razdoblje od kraja Drugog svjetskog rata do kraja 1980. godine se u Bugarskoj često smatra dosljednim i stabilnim razdobljem koje je objeležila vladavina jednog diktatorskog režima. Međutim, ovo razdoblje bugarske povijesti pokazalo se mnogo dinamičnijim i fragmentiranijim. Iskustva romske nacionalne manjine u Bugarskoj odražava složenost ove teme i oslikava nove političke tendencije u zemlji, kao i kontinuitet iz prošlosti.

Prijevod: Milica Kuzmanović i Daria Maracheva

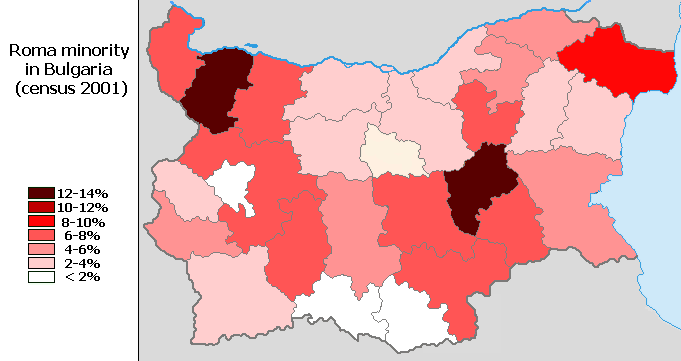

Godine 1946. udio romskog stanovništva u Bugarskoj iznosio je 2,4 % ili oko 170.000 ljudi koji su se izjašnjavali pripadnicima romske nacionalne manjine. Prije 1944. godine, odnosno tokom nacističkog režima u Sofiji, mnogi Romi pretrpjeli su institucionaliziranu diskriminaciju po osnovi nacionalne i vjerske pripadnosti. Tokom rata, Romima je bio zabranjen ulaz u središte glavnog grada i korištenje javnog prijevoza. Kako navodi Ulrich Büchsenschütz, u to vrijeme postojalo je nekoliko radnih logora u kojima je eksploatiran veliki broj Roma. Postoje podaci o sudjelovanju Roma u partizanskim jedinicama otpora i općenito u aktivnostima Bugarske komunističke partije u razdoblju prije rata.

Nakon 1945. godine, pokrenute su brojne inicijative u različitim područjima društvenog života u vezi s Romima. Osnovani su prvo romsko kazalište, novine Romano esi što u prijevodu znači ”Glas Roma”, otvorene su škole za Rome i osnovane mnoge udruge kulture. Nacionalne manjine su do određene razine bile prihvaćene od strane države, čime je država relativno osigurala njihovu relativnu lojalnost. Prema Ustavu iz 1947. godine:

Nacionalne manjine imaju pravo na obrazovanje na maternjem jeziku i na razvoj svoje nacionalne kulture [...]

Međutim, teško je utvrditi postojao li u ovim prvim godinama nakon političkih promjena opći stav Roma prema novom režimu. S jedne strane, po prvi put u Bugarskoj Romi su imali određenu zastupljenost, uključujući i člana parlamenta. S druge strane, postoji osnovana sumnja da su ustupke prema Romima od strane vlade bile uvelike simboličke i taktičke nego realne. U to vrijeme, mnogi Romi u Bugarskoj bili su muslimanske vjeroispovjesti i govorili su turski.

Vlada je smatrala takvu situaciju potencijalno opasnom, te je izašla s inicijativom izgradnje romske nacije kako bi ih udaljila od Turaka. Međutim, ovaj proces nikad nije poprimio solidan oblik. Romski jezik na primjer nikada nije bio priznat službenim jezikom ni na jednoj razini.

U svakom slučaju, razdoblje blagostanje nije trajalo dugo. Već početkom pedesetih godina prošlog stoljeća većina romskih udruga je raspuštena, a novine Romano esi, u međuvremenu preimenovane u Nevo Drom (“Novi put”), ukinute su. Autoritarne tendencije Narodne Republike su se učvrstile, a politika kulturne emancipacije i samouprave izgubila je zamah.

Ostale sfere života Roma nastavile su se mijenjati. Do 1946. godine, gradsko stanovništvo zemlje činilo je manje od 25% ukupnog stanovništva, osim toga postojalo je mnogo polunomadskih zajednica koje su zarađivale za život seleći se s jednog mjesta na drugo. Sovjetski model izgradnje proleterskog društva u Bugarskoj nije podržavao takav način života. Nomadizam i polunomadizam nisu bili u skladu s urbanističkim, industrijskim ekonomskim modelom i načinom život koji je promicala vlada.

Već sredinom pedesetih godina 20. stoljeća dogodio se veliki val naseljavanja polunomadskih zajednica. Pored Sarakatsani, skupina pastira s grčkog govornog područja, oko 20.000 romskih obitelji dobilo je zemlju i zajmove za izgradnju kuća. Tokom narednih desetljeća, mnogi Romi bili su smješteni u nove stambene blokove zajedno s etničkim Bugarima. Međutim, većina Roma bila je smještena u kuće koje su izgrađene u novim područjima što je rezultiralo formiranjem zasebnih romskih četvrti.

Međutim, vlada nije provodila samo stambenu politiku. Plan "modernizacije narodnog gospodarstva" podrazumijevao je uključivanje Roma u industrijsku radnu snagu. U pismu iz 1958. godine lokalnim stranačkim čelnicima, Odbor Bugarske Komunističke partije piše:

"Kao rezultat zanemarivanja i diskriminacije Roma u prošlosti od strane bugarske buržoazije, romsko stanovništvo je znatno zaostalo u svom razvoju [...] Romi nisu mogli naći stalni posao u sferi proizvodnje te su bili osuđeni na jako loš život, obavljajući tek slučajne poslove kako bi zaradili za život. Glad ih je natjerala da lutaju po cijeloj zemlji, a veliki broj Roma bio je prisiljen krasti i prositi. Romska djeca nisu imala priliku obrazovati se, te su nepismenost, neznanje i siromaštvo bili ih stalni pratilac."

Stoga su obrazovanje i zapošljavanje postavljeni kao glavni ciljevi kako bi Romi postali dio "narodnog marša ka svijetloj budućnosti". Kako su ti ciljevi ostvareni?

Jedan od instrumenata koji je država koristila bilo je osnivanje takozvanih "Osnovnih škola s poboljšanim radnim osposobljavanjem" (PSELT), koje su se pojavile oko šezdesetih godina dvadesetog stoljeća. Iako nisu bile zamišljene kao isključivo romske škole, postale su takve. Obrazovanje u takvim školama je uglavnom bilo usredotočeno na stjecanje profesionalnih vještina u područjima poput obrade metala, drveta, izrade cipela i garderobe kao i poljoprivrede.

Sljedeći korak koji je vlada poduzela bilo je uspostavljanje široke mreže školskih internata. Prema istraživanju koje je proveo Troebst i koje je objavljeno 1990. godine, u Bugarskoj je 1975. godine bilo 145 školskih internata u kojima je živjelo i studiralo oko 10.000 romske djece. Prema istraživanju koje je objavljeno 1995. godine, 10% od ukupnog broja ispitanih Roma pohađalo je školski internat. Međutim, ova politika podrazumijevala je visoku razinu segregacije. Osim što su školski internati gotovo isključivo pohađali Romi, oni su bili otvoreni i tokom ljeta, tako da je romska djeca bila potpuno odvojena od svojih obitelji. No, postavlja se pitanje dalo li provođenje ove politike ikakve rezultate u obrazovanju?

Od 1946. godine do 1992. godine, udio nepismenog stanovništva smanjio se s 81% na 11%. Krajem osamdesetih godina, većina Roma bila je zaposlena i imala je relativno jednak pristup zdravstvenoj skrbi. U usporedbi s razdobljem prije Drugog svjetskog rata, stambeni uvjeti romskog stanovništva su se znatno poboljšali.

Iako proleterska i socijalistička po svom imenu, Narodna Republika Bugarska je često izgledala suprotno od svog samoopisa. Odvajanje turskih i romskih vojnih obveznika u takozvane Građevinske snage bili su eksploatacija i šovinizam. Zabrana javnog izvođenja romske glazbe iz 1984. godine, izgradnja betonskih zidova oko romskih naselja i predstavljalo je sve osim politike koja promiče jednakost. Isto vrijedi i za političku zastupljenost Roma. Središnji odbor Bugarske komunističke partije nikada nije imao člana – pripadnika romske nacionalne manjine, iako su Romi druga najveća nacionalna manjina. Uslijed politike urbanizacije i naseljavanja, socijalna mobilnost također je bila ograničena. Uz vrlo rijetke iznimke, Romi su i dalje obavljali poslove s dna socijalne hijerarhije koja je trebala nestati u socijalističkom društvu.

Život Roma u Narodnoj Republici Bugarskoj obilježen je višestrukim kontroverzama i razvojem u različitim smjerovima. Nažalost, iako je došlo do određenih poboljšanja, Romi su i dalje bili izloženi diskriminaciji, a njihov glas se nije čuo. Romi su više bili objekt politike vlade, nego subjekt vlastite sudbine. Nažalost, tokom takozvane tranzicije, malo se promijenilo. Ekonomske nejednakosti u zemlji su porasle, a Romi su među prvima gubili posao. Zato nije neobično što su mnogi Romi nostalgični za prošlošću.

In September 1946, the monarchy in Bulgaria was officially abolished, the Communist Party took virtually full control over the country, and the state was declared a People’s Republic. The history of Bulgaria between the end of WWII and the late 1980’s is often narrated as a coherent and stable period, marked by the dominance of one dictatorial regime. However, this chapter of the history of Bulgaria proves to be much more dynamic and fragmented. The experience of the Roma minority in Bulgaria mirrors this complexity and reflects the new political tendencies in the country, as well as the continuities from previous times.

In 1946, the share of the Roma population in Bulgaria was around 2.4 per cent, which amounts to about 170 000 people who identified as Romani. Before 1944, when the Nazi- allied regime in Sofia was overthrown, many of these people suffered institutionalized discrimination based on ethnicity and religion. During the war, Roma were prohibited from entering the central areas of the capital city and to use public transport. According to Ulrich Büchsenschütz, there were several labour camps which exploited a great number of Roma interns. There are records for participation of Roma in the partisan resistance units and generally in the activities of the Bulgarian Communist Party in the period before the war.

After 1945, multiple Roma-related initiatives took place in various areas of social life. The first Roma theater was set up, the Romano esi (Roma voice) newspaper was established, schools for Roma were opened and many cultural organizations were formed. The minorities received some level of acceptance by the state and the state secured their relative loyalty. The constitution adopted in 1947 stated:

The national minorities have the right to receive education in their mother tongue and to develop their national culture […]

It is hard to determine, however, whether there was a common attitude of Roma towards the new regime in these first years after the political changes. On one hand, for a first time in Bulgaria, Roma found some representation in the country, including a member of the parliament. On the other, nonetheless, there is a strong suspicion that the curtsies done by the government were largely symbolic and more tactical than genuine. At the time, many Roma in Bulgaria were Muslim and spoke Turkish language. These circumstances were considered potentially dangerous in Sofia and the government therefore engaged in some sort of nation building for Roma in order to distance them from the Turks. This process, however, did not take any solid shape. The Roma language, for instance, was never recognized for official use at any level.

At any rate, the initial honeymoon period did not last too long. Already in the beginning of the 1950’s, most of the Roma organizations were dissolved and the Romano esi newspaper, in the meantime renamed Nevo Drom (New Path), was terminated. The authoritarian tendencies in the People’s Republic solidified and the politics of cultural emancipation and self-governance lost their momentum.

Other dimensions of Roma life in Bulgaria, however, continued to change. By 1946, the urban population in the country was less than 25 per cent and there were many semi-nomad communities who were earning their living by moving from one place to another. The Soviet model of building a proletarian society that took place in Bulgaria did not encourage, saying the least, such way of life. Nomadism and semi-nomadism were at odds with the urban, industrial economic model and lifestyle advanced by the government.

Already by the mid 1950’s a big wave of settlement of semi-nomad communities took place. Along with the Sarakatsani - a group of Greek-speaking transhumant shepherd communities - around 20 000 Roma families were given land and loans to build their own houses. Throughout the next decades many Roma were settled together with ethnic Bulgarians in the new housing blocs. The majority of Roma, however, were settled in houses in new areas, which led to the formation of separate Roma neighborhoods.

The housing policy, however, was not the only accent in the government’s strategy. The plan for the “modernization of the people’s economy” involved the inclusion of Roma into the industrial labor force. In a letter from 1958 to the local party leaders, the Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party writes:

“As a result of the attitude of neglect and discrimination towards this population in the past on the part of the Bulgarian bourgeoisie, the Gypsy population has lagged behind considerably in its development […] The Gypsies could not find permanent jobs in the sphere of production, and were doomed to lead a pitiful existence earning their living with chance work. Starvation forced them to wander all over the country, and a large number of them were forced to steal and beg. The children of the Gypsies had no opportunity to study and therefore illiteracy, ignorance and poverty were a constant companion to this population.”

Education and employment, therefore, were set as the main objectives for making Roma part of the “people’s march towards the bright future”. But how were these objectives achieved?

One of the tools employed by the state were the so-called “Primary Schools with Enhanced Labor Training” (PSELTs). These schools emerged in the 1960’s and although they were not necessarily designed as Roma schools per se, the PSELTs eventually became such. The education there was mostly focused on acquiring professional skills in the fields such as metalworking, woodworking, shoemaking, tailoring, and agriculture, to name a few.

Another policy of the government was the establishment of a wide network of boarding schools. According to a study conducted by Troebst and published in 1990, there were 145 boarding schools in Bulgaria in 1975, where around 10 000 Roma children were living and studying. A survey published in 1995 shows that 10 per cent of the surveyed Roma have attended a boarding school. This policy, however, involved a fair amount of segregation. Not only that the boarding schools were almost entirely attended by Roma, but they were also open during summer, so that the separation of Roma students from their families to be complete. But was there any educational effect of all these policies?

From 1946 to 1992 the share of the illiterate population shirked from 81 to 11 per cent. By the late 1980’s, the majority of Roma were employed and had relatively equal access to healthcare. In comparison with the period before WWII, Romani’s housing situation had significantly improved.

But although proletarian and socialist in name, the People’s Republic of Bulgaria often looked like the opposite of its self-description. The separation of the Turkish and Roma military conscripts in the so-called Construction Forces was an exploitative and chauvinistic in its nature policy. The 1984 prohibition of public performances of Roma music, the widespread construction of concrete walls around Roma settlements, and the violent name-changing campaign targeting the Muslim citizens of Bulgaria demonstrated everything but a vision of politics that promotes equality. The same applies for the political representation of Roma. The Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party never got a member from the Roma community, although that was the second most sizable minority in the country. Social mobility was also rather limited following the policies of urbanization and settlement. With very few exceptions, Roma continued to occupy professions at the bottom of the social hierarchy – something that was meant to fade away in a socialist society.

The life of Roma in the People’s Republic of Bulgaria was marked by a multiple controversies and developments in different directions. Sadly, regardless of the many improvements in their situation in this period, they continued to be discriminated and their voice was hardly ever heard. Roma have been more of an object of the government’s policies, than a subject of their own fate. Unfortunately, during the so-called “transition”, little changed in that regard. Yet, the material inequality in the country rose and Roma were among the first rendered unemployed. It is not surprising, in that sense, why so many Roma are nostalgic for the past.